Extract from The Guardian

There is more to the design of a potential LET – which is widely

expected to be included in the Finkel review – than whether it will

allow coal-fired generators to be included in the scheme

A wind turbine: under one model of an LET, one megawatt hour of zero emission power would attract 100% of a certificate. Photograph: Josh Wall for the Guardian

Michael Slezak

Thursday 8 June 2017 15.37 AEST Last modified on Thursday 8 June 2017 15.45 AEST

It is widely reported that the long-awaited Finkel review into the National Electricity Market will recommend (either as a first or second option) a Low Emissions Target to drive down emissions of the electricity sector, as well as give investors confidence to once again start spending money to build new generators.

In the discussion that has ensued, many reports have been hand-wringing about the “benchmark” set in the LET, and whether it would allow coal-fired power stations to generate low-emissions certificates – something that sounds rather perverse

But at least on the usual understanding of how a LET would work, this is mostly a red-herring. And there are more important things that Finkel, and the government, will be deciding on if they implement a LET.

Under this scenario, a baseline emissions intensity would be set – ie. the amount of CO2 that can be generated per megawatt hour of electricity, before a generator no longer receives any “Low Emissions Certificates”.

The figure widely mooted as either what Finkel will recommend, or what the government might accept, is 0.7 tonnes of CO2 per megawatt hour. The idea is that every megawatt hour of electricity produced by a generator that comes under that benchmark would receive some percentage of a “Low Emissions Certificate”.

That would exclude all existing coal power stations, but let in gas and other cleaner technologies.

So if a generator produced a megawatt hour of electricity that resulted in zero CO2 emissions (like those produced by wind and solar), the generator would receive 100% of a certificate.

On the other hand, if the megawatt hour produced 0.35 tonnes of CO2 (ie. at an intensity of half the benchmark), the generator would receive half a certificate. A generator that produced 0.6 tonnes of CO2 when generating that MWh would receive about 14% of a certificate – and so on.

Chief Scientist Dr Alan Finkel during Senate Estimates at

Parliament House on Thursday. Photograph: Lukas Coch/AAP

Just like with the existing Renewable Energy Target, retailers would then be required to purchase certificates from generators on an open market.

There has been much hand-wringing about whether the benchmark is 0.6 or 0.7, since 0.7 would technically allow the most efficient new-build coal (“HELE”) power plants to generate Low Emissions Certificates.

The system currently has an emission intensity of about 0.75. So if 0.7 was really a target, it would be no climate policy at all. (Modelling of do-nothing “business as usual” suggests it will reduce to under 0.7 by 2035 on its own.)

There is no reason why a benchmark set higher would be any worse for the environment, depending on other factors in the system’s design. Allowing existing coal generators to produce “low emissions” certificates might sound perverse, but it is the rest of the system that will drive emissions reductions – and a move away from coal, regardless of who has certificates.

It’s not enough to just have certificates generated. On its own, that will do nothing. Those certificates need to have a value to drive investment in low emissions generation – to incentivise the cleaner technology to produce more electricity.

To do that, the traditional discussion of a LET involves retailers being forced to buy a certain number of certificates for each megawatt hour of electricity they sell. By setting that number, just like with the RET, you can implement a specific target for the whole system.

If the government wanted the National Electricity Market to reduce its carbon intensity to 0.3, they can require retailers to buy enough certificates from generators, incentivising them to produce more low-emissions electricity.

The certificates are then bought and sold on an open market, driving investment in the lowest cost generation that meets the overall target.

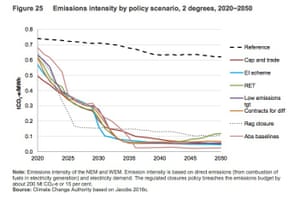

In fact, modelling of the impact of a LET by the Climate Change Authority has shown it could quite rapidly drive the emissions intensity of the electricity market much lower than that.

In their report from August 2016, Climate Change Authority modelled a LET with a benchmark of 0.6 tonnes of CO2 per MWh. They found it would rapidly reduce the emissions intensity of the National Electricity market.

With that benchmark – which is slightly lower than the figure reportedly being considered by Finkel – emissions intensity would drop to 0.1 tonnes of CO2 per MWh, shortly after 2030 and stabilise at about 0.5 after another decade or so.

Modelling used by Austrlaia’s Climate Change Authority of the

emissions intensity of Australia’s East-Coast National Electricity

Market under various potential policies including a Low Emissions

Target and an Emissions Intensity Scheme Photograph: Climate Change

Authority

Moreover, the CCA modelling found a similar effect would be brought about by many other policies, including an emissions intensity scheme.

It also found that the same emissions reductions could be produced, regardless of the benchmark used.

One key design feature is how scalable it is. The Paris Agreement requires that countries will “ratchet up” their emissions reduction commitments. So it is important that the policies that implement our commitments are also capable of ratcheting up.

It’s important to note though that although electricity is the biggest single contributor to Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, it still only accounts for 36% of total emissions and efforts in other areas, such as halting land clearing or improving fuel standards, can also contribute to meeting the Paris targets.

Where are Australia's emissions coming from?

Guardian graphic | Source: NGGI, NDEVR Environmental

The key issue that will determine that is how the overall target in the LET is set. If it’s set in the legislation, that will make it hard for a future Labor government – or any future government – to increase the policy’s ambition.

It’s also possible that the system-design recommended by Finkel could be completely differently than the LET modelled by the climate change authority, and discussed elsewhere. It’s also possible that the government will implement something completely different to what Finkel Recommends. If that’s the case, anything could go and we’ll just have to wait and see.

A wind turbine: under one model of an LET, one megawatt hour of zero emission power would attract 100% of a certificate. Photograph: Josh Wall for the Guardian

Michael Slezak

Thursday 8 June 2017 15.37 AEST Last modified on Thursday 8 June 2017 15.45 AEST

It is widely reported that the long-awaited Finkel review into the National Electricity Market will recommend (either as a first or second option) a Low Emissions Target to drive down emissions of the electricity sector, as well as give investors confidence to once again start spending money to build new generators.

In the discussion that has ensued, many reports have been hand-wringing about the “benchmark” set in the LET, and whether it would allow coal-fired power stations to generate low-emissions certificates – something that sounds rather perverse

But at least on the usual understanding of how a LET would work, this is mostly a red-herring. And there are more important things that Finkel, and the government, will be deciding on if they implement a LET.

One possible LET

There are many possible designs for the LET, but the one commonly discussed is very much like the existing Renewable Energy Target, but expanded to allow any type of generator into the scheme.Under this scenario, a baseline emissions intensity would be set – ie. the amount of CO2 that can be generated per megawatt hour of electricity, before a generator no longer receives any “Low Emissions Certificates”.

The figure widely mooted as either what Finkel will recommend, or what the government might accept, is 0.7 tonnes of CO2 per megawatt hour. The idea is that every megawatt hour of electricity produced by a generator that comes under that benchmark would receive some percentage of a “Low Emissions Certificate”.

That would exclude all existing coal power stations, but let in gas and other cleaner technologies.

So if a generator produced a megawatt hour of electricity that resulted in zero CO2 emissions (like those produced by wind and solar), the generator would receive 100% of a certificate.

On the other hand, if the megawatt hour produced 0.35 tonnes of CO2 (ie. at an intensity of half the benchmark), the generator would receive half a certificate. A generator that produced 0.6 tonnes of CO2 when generating that MWh would receive about 14% of a certificate – and so on.

Just like with the existing Renewable Energy Target, retailers would then be required to purchase certificates from generators on an open market.

What’s in a benchmark?

In most of the media discussion around the LET, you’d be forgiven for thinking the benchmark is the actual target for the emissions intensity of the National Electricity Market. But it is no such thing.There has been much hand-wringing about whether the benchmark is 0.6 or 0.7, since 0.7 would technically allow the most efficient new-build coal (“HELE”) power plants to generate Low Emissions Certificates.

The system currently has an emission intensity of about 0.75. So if 0.7 was really a target, it would be no climate policy at all. (Modelling of do-nothing “business as usual” suggests it will reduce to under 0.7 by 2035 on its own.)

There is no reason why a benchmark set higher would be any worse for the environment, depending on other factors in the system’s design. Allowing existing coal generators to produce “low emissions” certificates might sound perverse, but it is the rest of the system that will drive emissions reductions – and a move away from coal, regardless of who has certificates.

It’s not enough to just have certificates generated. On its own, that will do nothing. Those certificates need to have a value to drive investment in low emissions generation – to incentivise the cleaner technology to produce more electricity.

To do that, the traditional discussion of a LET involves retailers being forced to buy a certain number of certificates for each megawatt hour of electricity they sell. By setting that number, just like with the RET, you can implement a specific target for the whole system.

If the government wanted the National Electricity Market to reduce its carbon intensity to 0.3, they can require retailers to buy enough certificates from generators, incentivising them to produce more low-emissions electricity.

The certificates are then bought and sold on an open market, driving investment in the lowest cost generation that meets the overall target.

The impact of a LET

So the benchmark figure – of 0.7 or whatever it will be – is not a target for the electricity system.In fact, modelling of the impact of a LET by the Climate Change Authority has shown it could quite rapidly drive the emissions intensity of the electricity market much lower than that.

In their report from August 2016, Climate Change Authority modelled a LET with a benchmark of 0.6 tonnes of CO2 per MWh. They found it would rapidly reduce the emissions intensity of the National Electricity market.

With that benchmark – which is slightly lower than the figure reportedly being considered by Finkel – emissions intensity would drop to 0.1 tonnes of CO2 per MWh, shortly after 2030 and stabilise at about 0.5 after another decade or so.

Moreover, the CCA modelling found a similar effect would be brought about by many other policies, including an emissions intensity scheme.

It also found that the same emissions reductions could be produced, regardless of the benchmark used.

Other design issues that matter

Labor has indicated that they could support a LET, depending on some of the design features.One key design feature is how scalable it is. The Paris Agreement requires that countries will “ratchet up” their emissions reduction commitments. So it is important that the policies that implement our commitments are also capable of ratcheting up.

It’s important to note though that although electricity is the biggest single contributor to Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, it still only accounts for 36% of total emissions and efforts in other areas, such as halting land clearing or improving fuel standards, can also contribute to meeting the Paris targets.

Where are Australia's emissions coming from?

Blue: Electricity

Light Green: Stationary Energy (excluding electricity)

Dark Green: Transport

Pink: Fugitive Emissions

Red: Industrial Processes and Product Use

Light Orange: Agriculture

Orange: Waste

Light Blue: Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF)

Guardian graphic | Source: NGGI, NDEVR Environmental

The key issue that will determine that is how the overall target in the LET is set. If it’s set in the legislation, that will make it hard for a future Labor government – or any future government – to increase the policy’s ambition.

It’s also possible that the system-design recommended by Finkel could be completely differently than the LET modelled by the climate change authority, and discussed elsewhere. It’s also possible that the government will implement something completely different to what Finkel Recommends. If that’s the case, anything could go and we’ll just have to wait and see.

No comments:

Post a Comment