Jacobs Group modelling suggests clean energy target is also more

expensive than an energy intensity scheme

Economic modelling suggests the Finkel review’s clean energy

target would extend the life of coal-fired power plants. Photograph:

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Michael Slezak

Wednesday 14 June 2017 15.08 AEST Last modified on Wednesday 14 June 2017 15.33 AEST

The clean energy target recommended in the Finkel review does relatively little to reduce emissions, extends the life of coal power plants and is more expensive than the alternative energy intensity scheme, the modelling behind the report shows.

Released today, five days after the report itself, the economic models that inform the report reveal the main thing the policy achieves is giving some confidence to power generators – including coal power stations – so they can make informed decisions about investments.

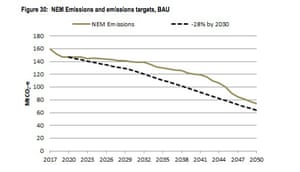

Alan Finkel commissioned Jacobs Group to do the emissions modelling. Their report shows that “business as usual” would result in emissions from the electricity sector falling in the years to 2030 – but not quite enough to meet the target that Finkel has set of 28% below 2005 levels.

Those cuts are driven by the existing renewable energy target, which runs until 2020, and then by the closure of existing coal-fired power plants as they reach the end of their life.

By instituting the clean energy target (CET), the modelling suggests emissions will fall more steadily, and will reach 28% – but that is only a little below what would be achieved by doing nothing.

Projected emissions from Australia’s National Electricity Market under business as usual, compared to a target of 28% below 2005 levels by 2030. Photograph: Jacobs Group

In that time, the modelling suggests a CET would give a boost to the coal industry – extending the life of existing plants.

Under business as usual, coal generation would drop suddenly by 2045 to a figure not seen until 2050 under the CET. However, under the CET, the reduction in coal generation would reduce gradually over the entire period, rather than drop suddenly in the 2040s.

By giving confidence to generators, investment decisions can be made over the longer term, meaning they can either maintain their infrastructure, or close it, resulting in a more gradual but long-lived existence for coal.

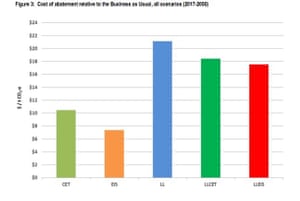

Underlying all this, the modelling also reveals that the CET, which Finkel recommended, is more expensive to the economy overall than the alternative approach – an emissions intensity scheme, which has been backed by almost every industry group as well as Labor.

“The lowest-cost options for the policy scenarios are for an EIS scheme, followed closely by the CET scheme,” the Jacobs modelling paper says.

The finding comes despite the energy and environment minister, Josh Frydenberg, saying on Wednesday on ABC Radio National that the emissions cut “has to be done before 2030, but it should be done with the lowest cost of abatement.”

In the report, Jacobs found the CET had a cost of abatement about 30% higher than an EIS – with each tonne of CO2 costing $10.50 to abate under a CET, rather than $7.50 under an EIS.

The cost of carbon abatement in Australia under several policy scenarios including an emissions intensity scheme (EIS) and a clean energy target (CET), according to modelling by Jacobs Group for the Finkel review. Photograph: Jacobs Group

However, the CET results in the lowest cost of electricity to both wholesale buyers and households, according to the modelling.

No comments:

Post a Comment