Extract from The Guardian

Critics

say public information film shows Shell ‘understood the threat was

dire, potentially existential for civilisation, more than a quarter

of a century ago’

Damian

Carrington and Jelmer Mommers

Tuesday

28 February 2017 16.45 AEDT

Climate

change “at a rate faster than at any time since the end of

the ice age – change too fast perhaps for life to adapt, without

severe dislocation”. That was the startling warning issued by the

oil giant Shell more than a quarter of a century ago.

The

company’s farsighted 1991 film, titled Climate of Concern, set out

with crystal clarity how the world was warming and that serious

consequences could well result.

“Tropical

islands barely afloat even now, first made inhabitable, and then

obliterated beneath the waves … coastal lowlands everywhere

suffering pollution of precious groundwater, on which so much farming

and so many cities depend,” says the film’s narrator, over

disturbing images of people affected by natural disasters and famine.

“In a crowded world subject to such adverse shifts of climate, who

would take care of such greenhouse refugees?”

The

film acknowledged the uncertainties in the computer model predictions

at the time, but noted the various scenarios had “each prompted the

same serious warning, a warning endorsed by a uniquely broad

consensus of scientists in their report to the United Nations at the

end of 1990”.

“What

they foresee is not a steady and even warming overall, but

alterations to the familiar patterns of climate, and the increasing

frequency of abnormal weather,” it cautioned. “It is thought that

warmer seas could make destructive [storm] surges more frequent and

even more ferocious.”

“Whether

or not the threat of global warming proves as grave as the scientists

predict, is it too much to hope as it might act as the stimulus –

the catalyst – to a new era of technical and economic cooperation?”

the film concludes. “Our numbers are many, and infinitely diverse.

But the problems and dilemmas of climatic change concern us all.”

A

family leaves their flooded home in Bangladesh. ‘In a crowded world

subject to adverse shifts of climate, who would take care of such

greenhouse refugees?’ says the film’s narrator. Photograph: Mufti

Munir/AFP/Getty Images

The

film was made for public viewing, particularly in schools and

universities, but is believed to have been unseen for many years. It

was remarkably prescient, according to Prof Tom Wigley, who was head

of the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia when it

helped Shell with the 1991 film.

“It

is amazing it is 25 years ago. Incredible,” he said. “It was

quite comprehensive on what might happen, what the consequences are,

and what we can do about it. I mean, there’s not much more.” He

said the predictions for temperature and sea level rises in the 1991

film were “pretty good compared with current understanding”.

“What

is really striking is nothing has happened [since] to make you doubt

the science as it was stated then,” said Tom Burke, at the green

thinktank E3G and a former member of Shell’s external review

committee.

Shell’s

1991 public information film, Climate of Concern. Photograph: the

Correspondant

But

Shell’s actions on global warming since 1991, such as major

investments in highly polluting tar sands and lobbying against

climate action, have been heavily criticised. In 2015, it was accused

of behaving

like a “psychopath” by the UK’s former climate change

envoy and of being engaged in a cynical attempt to block action on

global warming. Even its own former group managing director, Sir Mark

Moody-Stuart, said in 2015 it was “distressing”

that “remarkably little progress” had been made on

climate change by Shell and other oil companies.

The

revelation of the film,

obtained by the Correspondent, a Dutch online journalism

platform, and shared with the Guardian, has renewed the criticism.

“The

film shows that Shell understood that the threat was dire,

potentially existential for civilisation, more than a quarter of a

century ago,” said Jeremy Leggett, a solar power entrepreneur and

former geologist who had earlier researched shale deposits with Shell

and BP funding.

“I

see to this day how they doggedly argue for rising gas use, decades

into the future, despite the clear evidence that fossil fuels have to

be phased out completely,” he said. “I honestly feel that this

company is guilty of a modern form of crime against humanity. They

will point out that they have behaved no differently than their

peers, BP, Exxon and Chevron. For people like me, of which there are

many, that is no defence.”

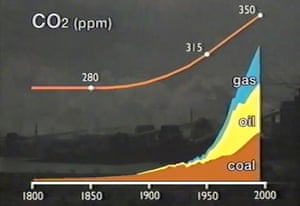

Shell’s

1991 film linked fossil fuel burning with rising atmospheric CO2 and

said the “serious warning” of dangerous warming was “endorsed

by a uniquely broad consensus of scientists”. Photograph: Climate

of Concern screengrab

Paul

Spedding, HSBC’s former global head of oil and gas and now at the

thinktank Carbon Tracker, said about half of Shell’s reserve base

is natural gas, the least carbon intensive of the fossil fuels.

“However, its oil portfolio could be a ticking tar-sands time bomb.

Tar sands, which make up nearly 30% of group oil reserves, are

significantly more carbon intensive than conventional oil. As things

stand, Shell’s oil production is destined to become heavier, higher

cost, and higher carbon, hardly a profile that fits the outlook

described in Shell’s video.”

Shell

had, in fact, known of the risks of climate change even earlier. A

“confidential” company report written in 1986, also seen by the

Guardian, noted the significant uncertainties in climate science at

the time but warned of the possibility of “fast and dramatic”

changes that “would impact on the human environment, future living

standards and food supplies, and could have major social, economic,

and political consequences”.

In

1989, Shell had already taken the effects

of climate change into account in the construction of an oil rig.

But in the same year, the so-called Global

Climate Coalition (GCC) was formed by the major oil

companies, including Shell’s US operation Shell Oil. It lobbied

hard to cast doubt on climate science and oppose government action,

and in 1998 Shell

withdrew, citing “irreconcilable” differences.

However,

Shell remained a member of another business lobby group that

campaigned against climate action, the American

Legislative Exchange Council, until 2015 and remains a

member of the Business Roundtable and American Petroleum Institute,

which both fought against Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan.

The

company has said it has remained a member of groups that hold

different views on climate action to

“influence” them. But Thomas O’Neill, from the group

Influence Map, which tracks lobbying, said: “The trade associations

and industry groups are there to say things the company cannot or

does not want to say. It’s deliberately that way.”

Shell

has also lobbied directly to undermine

European renewable energy targets, a sector it has invested in

although at a much lower level than oil and gas. In 2016, Shell

launched its New Energies division, with annual spending less

than 1% of the total $30bn Shell pumps into oil and gas.

Despite

the company’s public support since the 1990s for carbon taxes to

drive cuts in emissions, in 2015 it

lobbied for exemptions for the electricity it produces and uses,

particularly for its offshore oil and gas platforms.

Some

of Shell’s investments today are also criticised for being

incompatible with the 2C warming target agreed by the world’s

nations. A 2015

Carbon Tracker report concluded the company was planning to

invest more than $75bn in such projects over the following decade,

part of a “carbon bubble” in which reserves are being developed

that cannot be burned if climate change is to be halted – a concern

shared by the Bank

of England and World

Bank.

Another Carbon

Tracker report in 2016 cited a 1998 Shell document showing

the company was aware of this risk. “Shell knew about, but did not

act on, the risks of a carbon bubble,” the report said. “Looking

back over the last 20 years, it seems like Shell has gone backwards

in terms of transparency, and is still recycling the same old green

initiatives, and attempting to deflect responsibility in the face of

an existential threat to its business.”

Shell

was one of the first major oil companies to acknowledge the need to

act on climate change and has long argued that providing affordable

energy was vital for the world and its development. The 1991 film

anticipated the problem: “How could [developing] countries continue

to advance but leapfrog the energy-intensive face of development, by

which other nations prospered before its adverse consequences came to

light?”

But

in 2015

its own external review committee concluded Shell’s

sustainability report did not “adequately convey the urgency of

this [low-carbon energy] transition”. Earlier in February, Shell’s

CEO Ben van Beurden said: “We believe that climate change is real

and we believe that action will be needed.”

Moody-Stuart,

who was also chairman of Shell from 1998-2002, told the Guardian the

broad criticism of the company was unfair. “I don’t think enough

has been done, but I wouldn’t single out the oil industry.

Governments and others have some responsibility and Shell and others

have called for a price on carbon since the 1990s.”

“It

hasn’t got very far at all but that is not Shell’s fault,” he

said. “It is pretty unique for an industry to be actually asking

for something which will increase the price of their product, but

they are asking for it because that is what is needed to drive the

industry in the right direction.”

Burke,

a former head of Friends of the Earth, agreed there is a wider

problem. “It is too easy to blame it all on Shell for getting it

wrong”, he said, as there has been “a broader societal failure”.

Shell’s

1986 report said the climate change problem was one that “ultimately

only governments can tackle”. But it also noted, over three decades

ago, that the energy industry “has very strong interests at stake

and much expertise to contribute. It also has its own reputation to

consider, there being much potential for public anxiety and pressure

group activity.”

No comments:

Post a Comment