Extract from The Guardian

On New Year’s Day 1923 a white woman was beaten

and residents of Sumner, Florida, claimed her assailant was black –

which sparked race riots where the casualties were mostly black and

hate wiped out a prosperous town

The ruins of the

two-story shanty near Rosewood, Florida, in 1923 where black

residents barricaded themselves and fought off a band of whites.

Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

Jessica

Glenza in Cedar Key, Florida

Monday 4 January 2016 00.00 AEDT

Four black schoolchildren raced home along a dirt

road in Archer, Florida,

in 1944, kicking up a dust cloud wake as they ran. They were under

strict orders from their mother to run – not lollygag or walk or

jog, but run – directly home after hitting the road’s curve.

The littlest, six-year-old Lizzie Robinson (now

Jenkins), led the pack with a brother on each side and her sister

behind carrying her books.

“And I would be [running], my feet barely

touching the ground,” Jenkins, now 77, said at her home in Archer.

Despite strict adherence to their mother’s

orders, the siblings weren’t told why they should race home. To the

children, it was one of several mysterious dictates issued during

childhood in the Jim Crow south.

As Jenkins tells it, the children didn’t know

why Amos ’n’ Andy was often interrupted by revving engines and

calls from her father to “Go upstairs now!”, or why aunt Mahulda

Carrier, a schoolteacher, fled to the bedroom each time a car drove

down their rural road.

Explanations for demands to hide came later, when

Jenkins’s mother, Theresa Brown Robinson, whispered to her daughter

the story of violence that befell the settlement of Rosewood in 1923.

The town was 37 miles south-east of Archer on the

main road to the Gulf. Carrier worked there as the schoolteacher,

while living with her husband Aaron Carrier. On New Year’s Day

1923, a white woman told her husband “a nigger” assaulted her, a

false claim that precipitated a week of mob violence that wiped the

prosperous black hamlet off the map, and led to the near lynching of

Aaron Carrier.

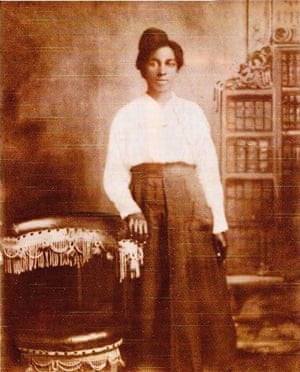

Mahulda Carrier, a schoolteacher, fled to the

bedroom each time a car drove down their rural road. Photograph:

Lizzie Jenkins

Jenkins now believes that all of it – the

running, calls to go upstairs, her aunt fleeing to the bedroom –

was a reaction to a message her parents received loud and clear:

don’t talk about Rosewood, ever, to anyone.

But after Jim Crow laws lifted, and lynch mob

justice was no longer a mortal threat, survivors did begin to talk.

So egregious were the stories of rape, murder, looting, arson and

neglect by elected officials, that Florida investigated the claims in

a 1993 report.

That led to a law that eventually compensated then

elderly victims $150,000 each, and created a scholarship fund. The

law, which provided $2.1m total for the survivors, improbably made

Florida one of the only states to create a reparations program for

the survivors of racialized violence, placing it among federal

programs that provided payments to Holocaust survivors and interned

Japanese Americans.

News of Florida’s reparations program ran

nationwide when it was passed in 1994, on the front page of the Wall

Street Journal among others. Hollywood picked up the tale. Don

Cheadle starred in a 1997 film about the pogrom. Several books were

written about Rosewood.

Though the legislation was never called such, the

program now represents one of just a handful of reparations cases in

the United States, as calls to compensate victims of racialized

violence have grown louder in the last two years.

2015 brought renewed calls to compensate victims

of race-related violence from college students, theologians and

criminal justice advocates. The city of Chicago started a $5.5m

reparations fund for the more than 100 victims tortured at the

hands of police commander Jon Burge.

Last month, students at Georgetown University

demanded that the administration set

aside an endowment to recruit black professors equal to the

profit from an 1838 slave sale that paid off university debt. The 272

slaves were sold for $400 each, the equivalent of about $2.7m today.

One day after protests began, students successfully renamed a

residence hall named after Thomas Mulledy, the university president

who oversaw the sale (it was renamed Freedom Hall).

At least one progressive Christian theologian is

pushing

Protestants to reckon their own history with slavery with

reparations. In 2014, Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates breathed fresh

life into the debate in his widely lauded article The

Case for Reparations.

Rosewood burning

Where Rosewood once stood is now little more than

a rural scrubland along state road 24, a lonely highway in central

Florida bordered by swamp, slash pine and palmetto. A placard on the

side of the road describes the horror visited upon the hamlet.

But in 1923, the settlement was a small and

prosperous predominantly black town, with its own baseball team, a

masonic temple and a few hundred residents. It was just three miles

from the predominantly white town of Sumner, and 48 miles from

Gainesville.

A black resident’s home is shown in flames

during the race riots in 1923. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

On New Year’s Day 1923, white Sumner resident

Fannie Taylor was bruised and beaten when her husband returned home.

The Taylors were white, and the residents of Sumner were in near

universal agreement that Fannie’s assailant was black.

A crowd swelled in Sumner to find the “fugitive”,

some from as far away as Gainesville, where the same day the Klu Klux

Klan held a high-profile parade. Over the next seven days gangs of

hundreds delivered lynch mob justice to the once-affluent town of

Rosewood.

“I blame the deputy sheriff,” Robie Mortin, a

Rosewood survivor, told the Seminole

Tribune in 1999. “Because that lady never dropped a name as to

who did what to her. Just said a negro, black man. But when the

sheriff came along with his posse and everything, he put a name to

the person: Jesse Hunter.”

Mortin died in 2010 at age

94 in Riviera Beach, Florida. She was believed to be one of the

last survivors of the New Year’s riots in 1923. After years of

silence she became one of the most vocal. Though Florida completed an

investigation into the events that took place in Rosewood, some

narratives remain disputed.

“They didn’t find Jesse Hunter, but noticed

that here’s a bunch of niggers living better than us white folks.

That disturbed these people,” Mortin said. Her uncle, Sam Carter,

is believed to have taken the man who beat Taylor, a fellow Mason, to

safety in Gulf Hammock, a few miles away. When Carter returned he was

tortured, shot and lynched by the mob looking for Taylor’s

assailant.

“My grandma didn’t know what my uncle Sammy

had done to anybody to cause him to be lynched like that,” Mortin

told the Tribune. “They took his fingers and his ears, and they

just cut souvenirs away from him. That was the type of people they

were.”

Carter is believed to be the first of eight

documented deaths associated with the riots that would worsen over

the next three days.

The Levy County sheriff, Bob Walker, holds a

shotgun allegedly used by Sylvester Carrier, black resident of

Rosewood, to shoot and kill two deputized white men who were at his

door in 1923. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

The settlement itself was wiped off the map.

Several buildings were set on fire just a few days after New Year’s,

and the mob wiped out the remainder of the town a few days later,

torching 12 houses one by one. At the time, the Gainesvile Sun

reported a crowd of up to 150 people watched the dozen homes and a

church set ablaze. Even the dogs were burned.

“The burning of the houses was carried out

deliberately and although the crowd was present all the time, no one

could be found who would say he saw the houses fired,” a Sun report

said, describing the scene.

At least two white men died, including CP “Poly”

Wilkerson of Sumner and Henry Andrews of Otter Creek, when they

attempted to storm a house Rosewood residents had barricaded

themselves in.

A state report on the violence

identifies murdered black Rosewood residents as Sam Carter, matriarch

Sarah Carrier, James Carrier, Sylvester Carrier and Lexie Gordon.

Mingo Williams, a black man who lived nearby, was also killed by the

mob.

Aaron Carrier, Mahulda’s husband and Jenkins’s

uncle, was nearly killed when he was dragged behind a truck and

tortured on the first night of the riots. At death’s door, Carrier

was spirited away by the Levy county sheriff, Bob Walker, she said,

and placed in jail in Bronson as a favor to the lawman.

Mahulda was captured later the same night by the

mob, Jenkins said, and tortured before Walker eventually found her.

“They got Gussie, that was my aunt’s name,

they tied a rope around her neck, however they didn’t drag her,

they put her in the car and took her to Sumner. Don’t know if you

know – a southern tradition is to build a fire … and to stand

around the fire and drink liquor and talk trash,” Jenkins said.

“So they had her there, like she was the

[accused], and they were the jury, and they were trying to force her

into admitting a lie. ‘Where was your husband last night?’ ‘He

was at home in bed with me.’ They asked her that so many times so

she got indignant with them … And they said, ‘She’s a bold

bitch – let’s rape the bitch.’ And they did. Gang style.”

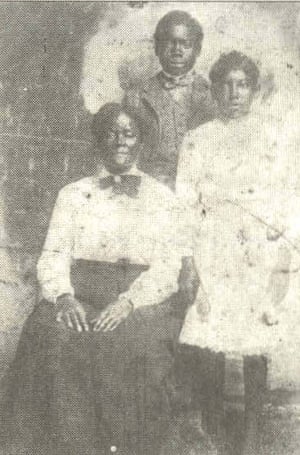

Sarah Carrier, left, Sylvester, standing and

Willie Carrier, right. Photograph: Public Domain

Another Rosewood resident, James Carrier, was shot

over the fresh graves of his brother and mother after several men

captured and interrogated him. He was first told to dig his own

grave, but couldn’t because two strokes had paralyzed one arm. The

men left his body splayed over the graves of his family members.

But despite widespread coverage of the incident –

the governor was even notified via telegram – the state did

nothing.

Not for one month, when it appears a feeble

attempt to indict locals was made by a grand jury, after all the

residents of Rosewood had long fled into the nearby swamps and

settlements of central Florida.

The oral history of Rosewood was a secret, passed

through several families with each recipient sworn to silence, as

black Americans endured decades of terror in Florida. When Jenkins

was six her parents would have had fresh memories of lynchings.

From 1877 to 1950, the county where the Robinsons

lived, Alachua, had among the largest sheer volume of lynchings of

any community in the nation, according to the Equal Justice

Initiative. Per capita, Florida lynched more people than any other

state. And counties surrounding Alachua were not friendlier.

Hernando, Citrus, Lafayette and Taylor counties

had some of the highest per capita rates of lynchings in the country.

By volume, nearby Marion and Polk counties had among the most in the

US. Legislation, reparations and state reckons with ugly past

The story only came to light in 1982, after a

reporter at the then St Petersburg Times exposed the forgotten riot.

The reporter, Gary Moore, had traveled to Cedar Key, 10 miles

south-west of Rosewood on the coast, to explore a Sunday feature on

the rural Gulf town.

“Like the public at large, I personally had

never heard of Rosewood,” Moore wrote in a synopsis of research

published in the 1993 report that was submitted to the Florida Board

of Regents. “I held dim assumptions that any such incident would

long ago have been thoroughly researched and publicized by

historians, sociologists, anthropologists, advocacy organizations, or

others.”

A crowd of white citizens of Sumner, near the

scene, are shown in 1923. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

That it wasn’t, Moore blamed on “psychological

denial” and “blindness”.

“There were many things thought better left

unquestioned,” Moore reasoned.

By 1993, before the report was issued, Moore’s

story had made a wide impact, becoming a 60 Minutes documentary and

earning follow-ups by other news outlets. Moore, however, recounted

in detail his struggle for academic and political acceptance of the

narrative, and said even 11 years after his story appeared many

attempted to deny the massacre occurred.

One of Moore’s sources, Arnett Doctor, would

later devote much of his life to lobbying for Rosewood reparations.

Doctor, a descendant of survivors, spent untold hours eliciting

detailed narratives of the event from survivors. He is often cited as

the “driving

force” behind the reparations bill, as the man who brought his

findings to high-powered attorneys at Holland & Knight, who

helped lobby the legislature for reparations.

Doctor died at the age of 72 in March 2015, in

Spring Hill, Florida, a few hours south of Rosewood.

“We deliberately avoided anything but

compensation for the losses they incurred,” said Martha Barnett, an

attorney at Holland & Knight who helped lobby the Florida

legislature on behalf of the survivors of Rosewood. Barnett said the

term “reparations” can’t be found in the law passed in Florida.

Instead, attorneys focused on private property

rights. She said she and other attorneys needed “to make it

something legislators could find palatable in the deep south some

20-some years ago”.

Barnett said the then Democratic governor, Lawton

Chiles, promised his support from the beginning. By April 1994, the

House

passed a bill to compensate victims of the attack with a 71-40

vote. Four days later, on 9 April 1994, the Senate

passed a matching bill with a vote of 26-14, to cries of “Praise

the lord!” from those Rosewood descendants present.

Rosewood was 37 miles south-east of Archer on the

main road to the Gulf. Photograph: Jessica Glenza

“It’s time for us to send an example, a

shining example, that we’re going to do what’s right – for

once,” Democratic senator Matthew Meadows said at the time. Chiles

died less

than four years after signing the bill.

Now, near Rosewood, Rebel flags are common.

Businesses bear the name, and some locals would be as happy to again

forget the incident.

Information on the pogrom is notably muted in some

local historical societies.

“What it takes to make someone whole, what it

takes to repair the past, is probably different for every person, and

some things are more effective than others,” said Barnett.

Many of the survivors invested the money they

received into their homes. Willie Evans, 87 when he received the

$150,000 payment in 1995, put a new

roof, windows and doors on his home. Mortin considered traveling

to Greece. Jenkins’s mother, who received $3,333.33 from the fund,

placed ledgers on the graves of her sister, three brothers and

parents.

“The thing that mattered most to [survivors] was

that the state of Florida said, ‘We had an obligation to you as our

citizens, we failed to live up to it then, we are going to live up to

it today, and we are sorry,’” Barnett said.

For Doctor, whose own identity seemed wrapped up

in the Rosewood story (the license plate on his truck read

“ROSEWOOD”),

even the unique success of the legislation was not enough. He dreamed

of rebuilding the town.

“The last leg of the [healing process] is the

redevelopment and revitalization of a township called Rosewood,”

Doctor told the Tampa

Bay Times in 2004, as the plaque along State Road 24 was

dedicated by then governor Jeb Bush. “If we could get $2bn, $3bn of

that we could effect some major changes in Levy County.”

No comments:

Post a Comment