Extract from The Guardian

Rich countries say they are on track to beating

the $100bn climate fund target, but poorer countries criticise the

unfair burden of loans and a stark lack of money for adaptation

The problem of the $100bn is not whether it will

be reached – it almost certainly will – but how. Photograph:

Patrick Aventurier/Getty Images

Friday 4 December 2015 23.55 AEDT

Poor countries at climate talks in Paris have

railed against an attempt to water down assistance promised to help

them overcome the climate crisis they did not cause.

Rich countries are committed to provide $100bn

(£66bn) to developing countries by 2020. More than any other, this

figure will decide the fate of the talks billed to stop climate

change.

On Wednesday, US special envoy for climate change

Todd Stern had told a press conference that donor countries were

“well

on the way to beating that pledge”.

Stern said a “conservative”

report compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD), a thinktank sponsored by the richest countries on

Earth, in October “showed on the basis of 2014 numbers we are

around $62bn, probably a little bit more than that”.

For the period between now and 2020, he said:

“There have since that time been a number of pledges made both by

individual countries... I think if you look at all of those pledges,

plus what the OECD

have already totalled up... we are at a pretty high number, both

where we are now and where we’ll be over the next few years.”

And yet the problem of the $100bn is not whether

it will be reached – it almost certainly will – but how. There is

an

almighty gap between how the developing and developed worlds

define what counts as adequate climate assistance.

Within the monies the OECD counted as climate

finance was a vast range of loans, grants and aid relabelled as

climate-related, much of which developing countries do not see as

assistance but investment. On top of this, the OECD model adds in the

private capital “mobilised” by the trickle of public cash.

For example, Germany and France have promised to

increase their 2020 finance to $4.47bn and $4bn respectively. Yet

despite the similar numbers, grant-making Germany is seen as a leader

and money-lending France a villain.

For developing countries, loans are a particularly

problematic aspect of this methodology. Gambia’s environment

minister, and representative of the least developed countries group,

Pa Ousman Jarju said: “We cannot take loans to pay for climate

change and take that as climate finance. For us it needs to be

grant-based finance because we are not responsible for what is

happening.”

Stern’s upbeat analysis was scorned by Nozipho

Mxakato-Diseko, the South African chair of the Group

of 77 and China, who speaks for the poorest 134 countries in the

negotiations. She called the OECD report a “mirage” that was

being used to create the illusion of a finance process on the right

track.

“We had been asking for work to be done by the

[UN] standing

committee on finance. An institution of the convention. And every

time we asked, those requests were refused,” said Mxakato-Diseko.

Instead, she said, wealthy countries had elevated

the methodology of a thinktank to de facto UN climate policy, without

consultation.

“We woke up to find that we had a report that

was telling us that we were accomplishing [$100bn]. We were not aware

of that report. We were not aware that countries had mandated that

report,” she said.

Oxfam’s climate policy adviser Jan Kowalzig

said: “It’s deeply concerning that a donor-driven methodology

like that of the OECD is being used to champion rich country climate

funding [as being] at a pivotal stage in sealing a climate deal. The

system is far from perfect and, critically, is based on donor

countries’ choices on what and how to count, allowing funding

levels to look higher than they actually are.”

There is just one day of talks left before

negotiators must hand over a workable draft to their various

ministers for the second phase of deal-making. For the US, using the

OECD methodology puts the talismanic $100bn within reach, defusing an

issue insiders say has become utterly intransigent.

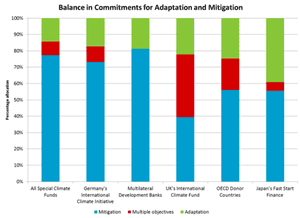

A second tortured sore is the balance between

funding for “adaptation” – coping with the effects of climate

change – and “mitigation”, carbon cutting interventions.

Mitigation tends to attract vastly more finance because its profile –

renewable energy, forestry, agriculture - comes with readymade

business models and can convince private capital to provide

additional help. Because of this, mitigation attracts roughly three

quarters of all climate finance.

Adaptation and mitigation in climate finance

Photograph: WRI

Adaptation, much of which involves improving

infrastructure, offers no such ready profit model and generally

requires grants. The African negotiating bloc has called for

adaptation finance to reach $32bn a year by 2020. But Kowalzig said

that even with new pledges, public adaptation money was only likely

to amount to $5-8bn per year in 2020.

“If today’s public adaptation finance were

divided among the world’s 1.5 billion smallholder farmers in

developing countries, they would get around $3 each year to cope with

climate change – the price of a cup of coffee in many rich

countries,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment